Summary

Here’s a summary in case you just got a scary AWS bill:

I received an AWS bill for $2,700, which was much higher than expected. I traced the high bill to a 13GB disk image that he had stored in an S3 bucket and exposed through a CDN. The CDN was trying and failing to cache the disk image, which was causing high bandwidth utilization.

I contacted AWS support, and they were able to waive the bill. This will likely be the case with you as well if this is the first time this has happened to you. AWS also explained that I could have avoided the high bill by setting the bucket to private and not using a CDN (an S3 best practice; but in this case the bucket was intentionally public for various reasons).

My experience highlights the importance of understanding how AWS billing works and how to control your costs. He also recommends using a cloud cost management tool to help you track your spending.

Update

I joined Rob Hirschfeld on the The 2030 Cloud where we discussed some additional behind the scenes investigatory work that went on by a nameless Amazon Web Services (AWS) employee.

Scene

It was a bright, Saturday morning, July 4, 2020. I had just gotten Max all situated with breakfast and cartoons (Mighty Mike, if you’re curious). Julie was sleeping in like she usually does on every day I have off. I’m an early riser and this is a cherished part of our co-parenting. It gives Max and I time to bond (when he’s not stuffing his face and laughing at cartoons). I sat down with my laptop to plow through the week’s personal email.

The e-mail

“Oh look, the AWS bill, I should have a laugh at that,” I thought to myself. Until recently, it had been pennies a month for some very light SES usage. In February, I moved off Google Cloud back to AWS. The primary motivation was that Google had so intertwined GSuite and GCP IAM that it became overly confusing.

Along with that migration came the CDN for this web site (cdn.chrisshort.net). I mean a Cloudflare fronted S3 bucket that holds assets deemed too big for git when I say CDN. It’s not even ChrisShort.net itself, as it is hosted on Netlify’s CDN and every other static site I own or manage. I’ve been a Cloudflare user for a long time. The CDN is less than 300 files and has existed for over five years on various clouds. Moving it back to AWS from GCP bumped the AWS bill to an average of $23/month. Not too bad given the site’s traffic.

The shock

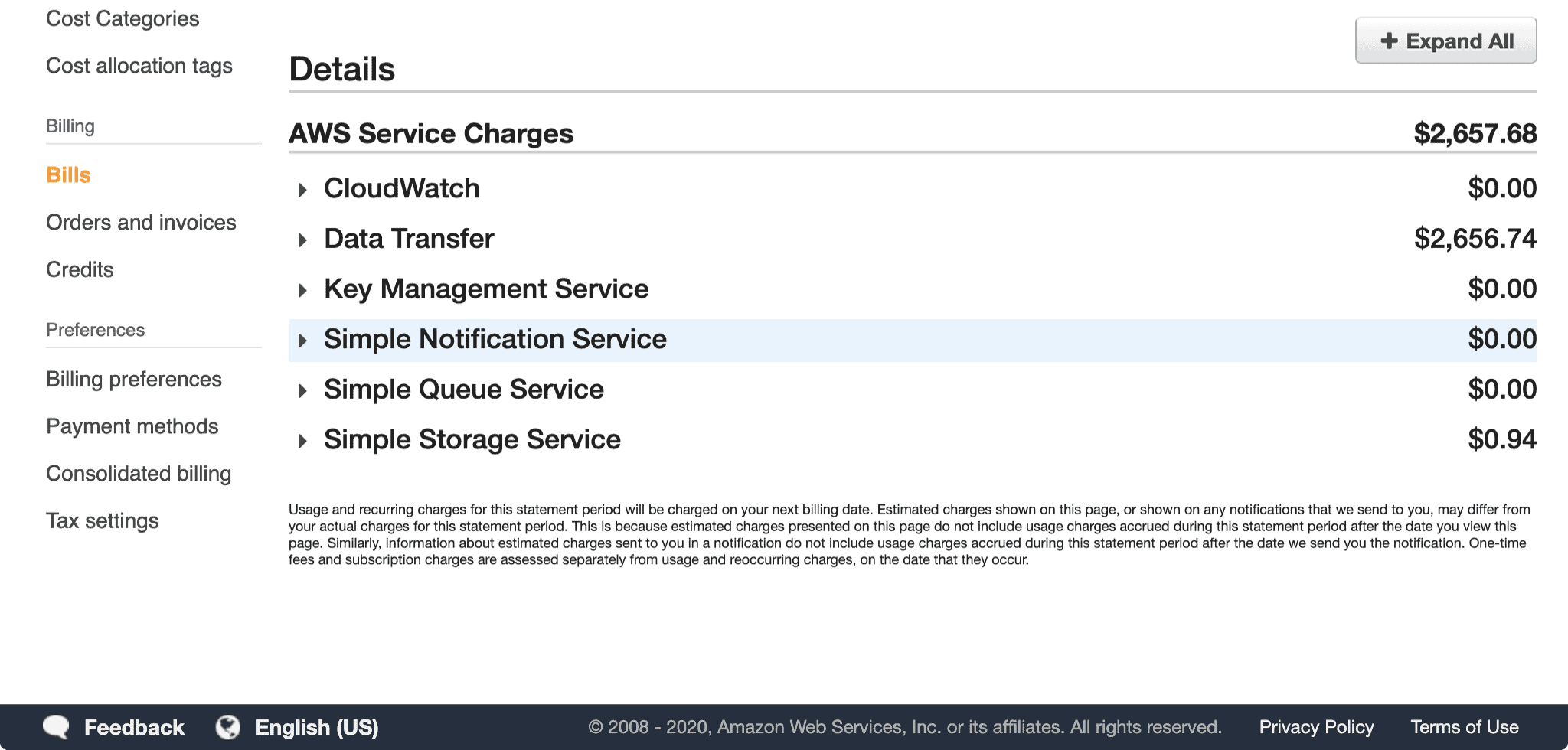

Not on this Saturday morning, nope. June 2020’s AWS bill was a heart palpitation causing $2,657.68 (JPG). I audibly gasped, “Keep your shit together.” I thought to myself. Max was leaned up against me drinking his milk. I know he could tell something was wrong because he looked at the laptop screen. I only assume when he saw letters and numbers, he thought, “Adult stuff… These cartoons and this Cinnamon Toast Crunch tho.” 2020 being the year that it is and my military history being what it is, I’ve been diagnosed with a panic disorder (on top of the PTSD and physical injuries).

The panic

Good morning, $2700 AWS bill!

— Chris "Not So" Short (@ChrisShort) July 4, 2020

Holy shit...

I immediately began having a panic attack. As I took the mental steps to mitigate the onset of the panic attack, I started forming a battle plan. Yes, I can switch back to emergency mode, like back in the old days, when something would go bang or boom, and I’d run towards it (it’s not helpful overall, trust me).

First, Max: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs? Check. Next, me: As if it was destined, my alert for morning medications went off.

“Daddy’s gotta grab his meds, bud.” Instinctively, Max leans off me (wow… okay… he’s used to hearing that reminder and statement shortly after that; my brain is now in overdrive). I take everything I need to conquer this while still being able to function cognitively. I refill my coffee and grab a laptop charger.

Incident response

Check the source of truth.

What’s diverged?

How do we get things back to normal?

I login to the AWS console, hoping I got some output that was uniquely off this month. Weirder stuff has happened (like S3 going down). This bill couldn’t be more out of the norm than ever. This AWS bill is several hundred dollars more than our mortgage! I hit the AWS Billing page and am deeply saddened by what I see:

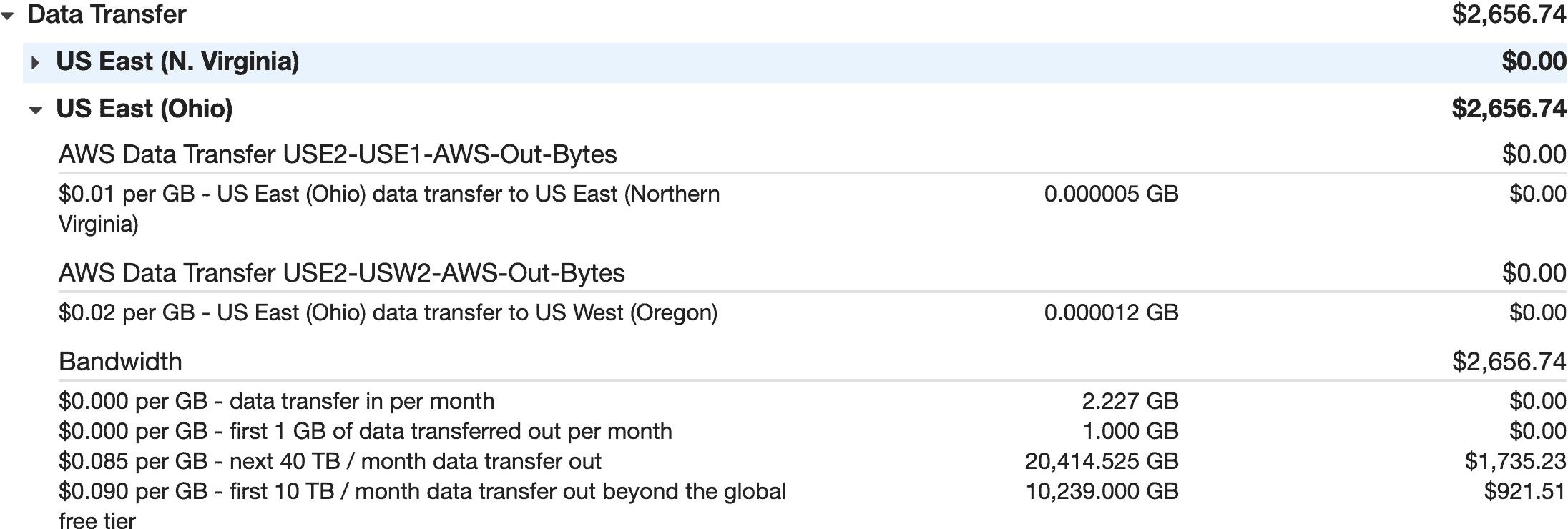

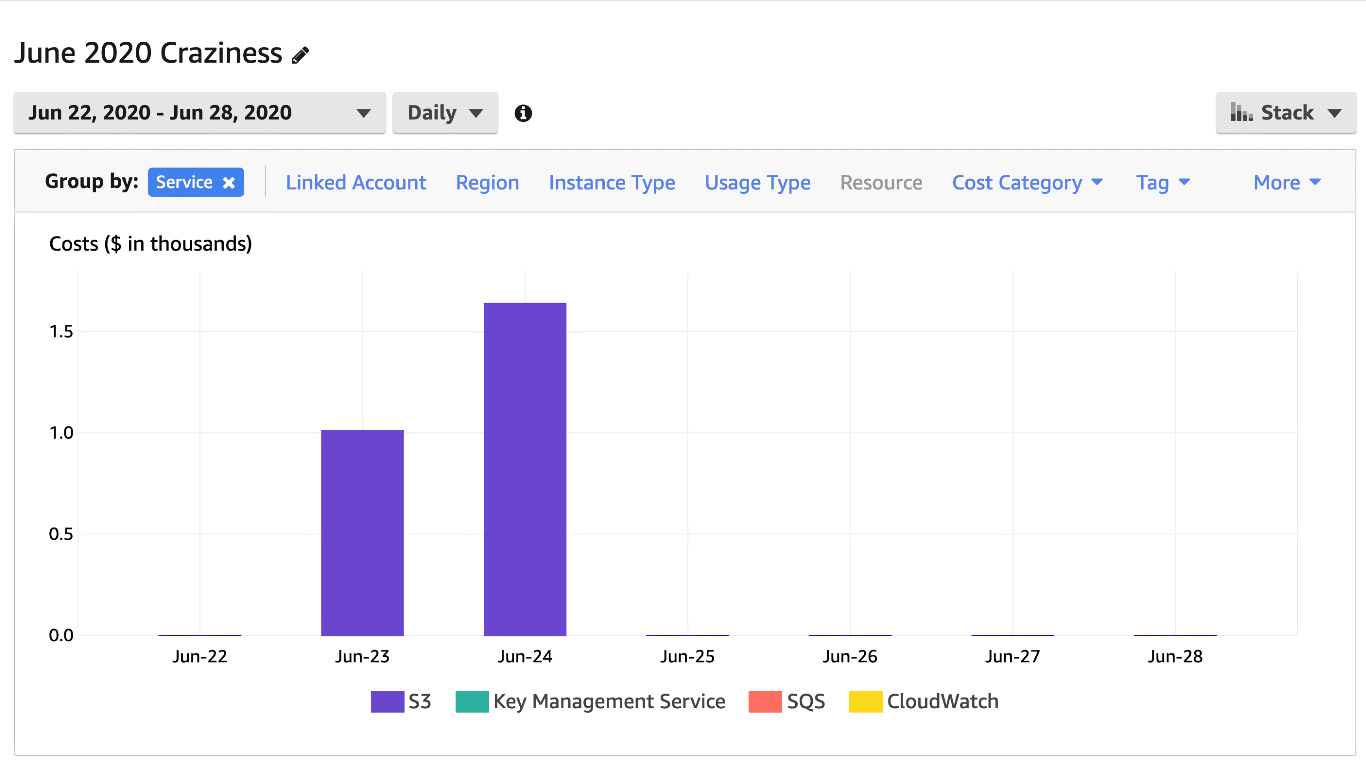

There it was. $2,657.68, staring at me. “This can’t be legit.” Drilling down even further, it looks like it is indeed legitimate traffic from the cdn.chrisshort.net S3 bucket in us-east-2. In total, more than 30.6 terabytes of traffic had moved out of that one S3 bucket. WHEN?!? Did this just happen? Nope.

30.6 TB?!?! how is that even possible??? $1,011.59 on 23 June 2020. $1,639.07 on 24 June 2020.

I immediately open a ticket with AWS Support frantically wondering what broke? How is this even possible? Did someone bypass Cloudflare? What the hell is Cloudflare saying?

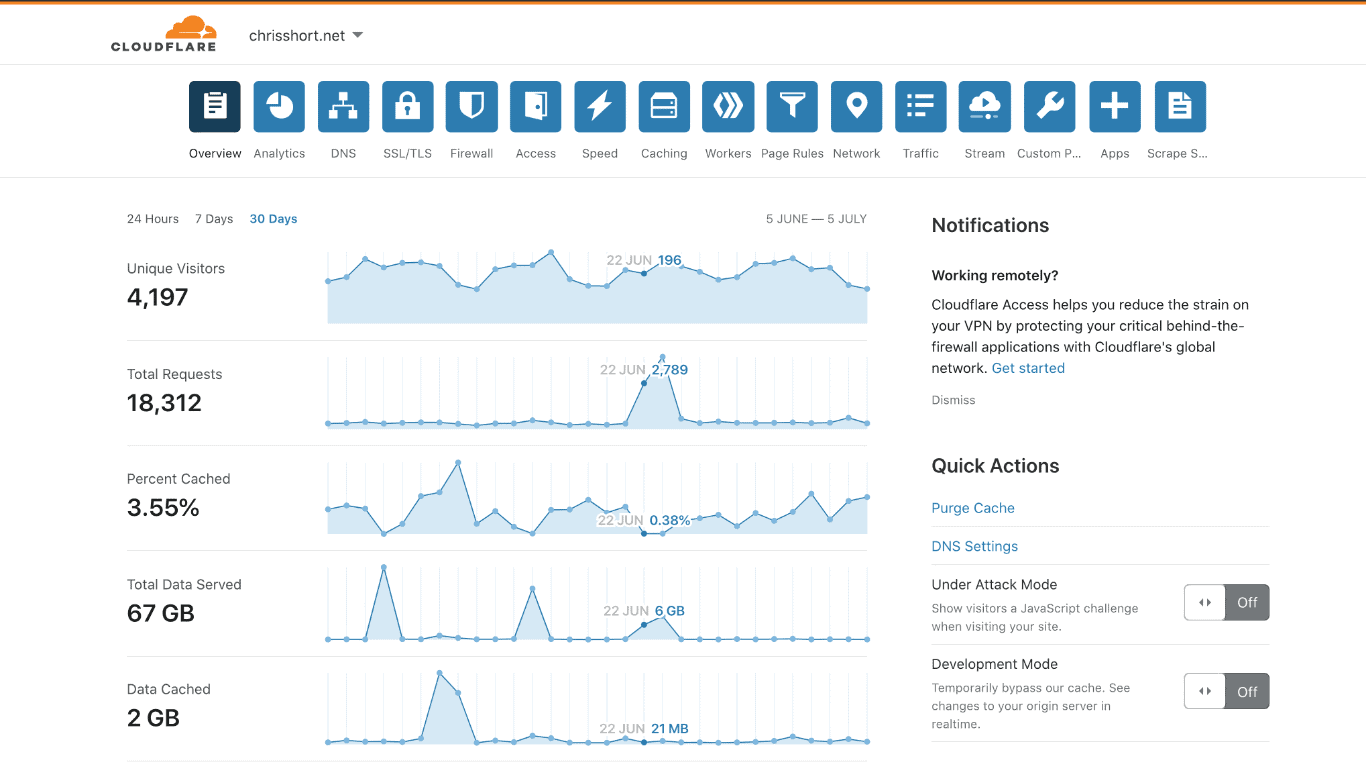

Oh cool, Cloudflare let those 2,700 requests passthrough completely uncached? How is that not anomaly detected as a DDoS??? How is it that barely a fraction of the traffic is cached (more on that later)?

Oh cool, Cloudflare let those 2,700 requests passthrough completely uncached? How is that not anomaly detected as a DDoS??? How is it that barely a fraction of the traffic is cached (more on that later)?

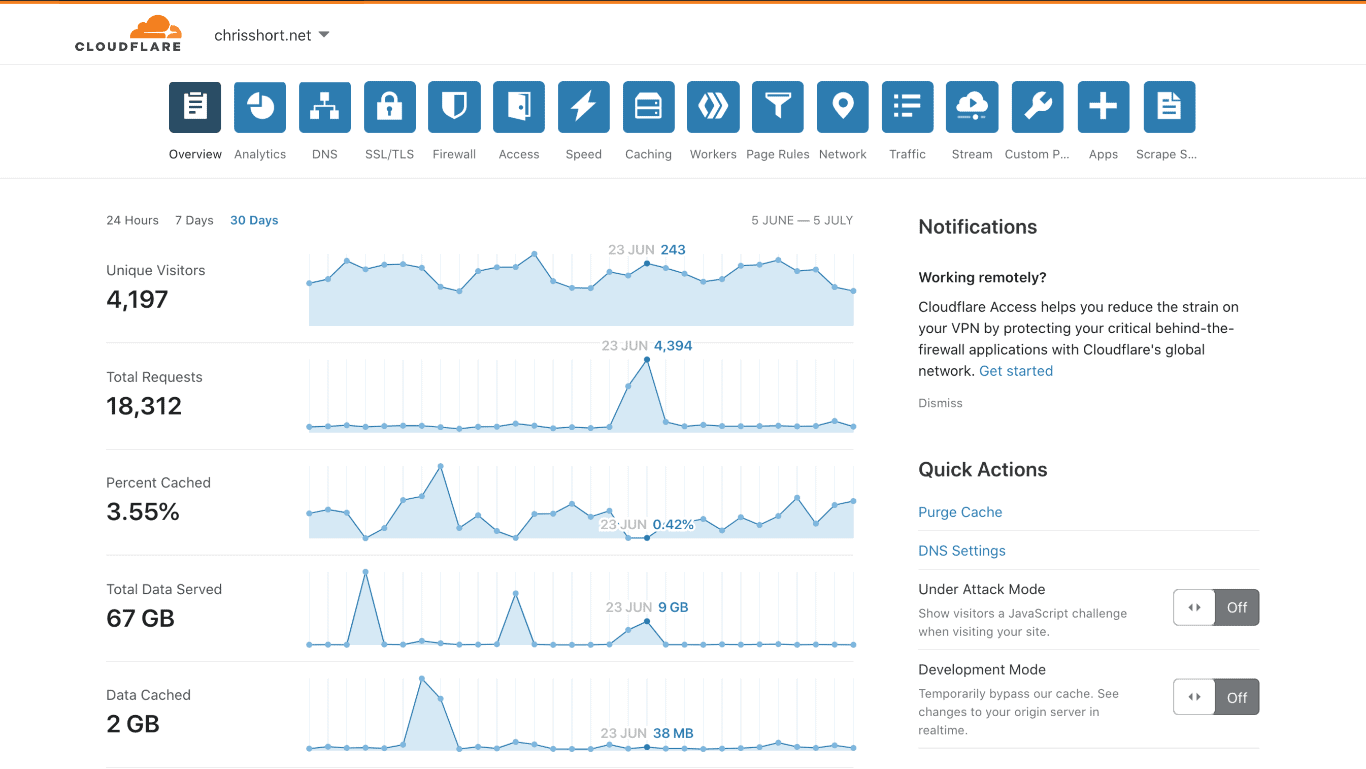

Oh, another 4,400 requests the next day… Sweet, baby Jesus. Oh, but you served 9 GB from cache. Thanks, Cloudflare.

Oh, another 4,400 requests the next day… Sweet, baby Jesus. Oh, but you served 9 GB from cache. Thanks, Cloudflare.

Help Arrives

Apparently, when you tweet something crazy af, like a $2700 AWS bill, it gets a lot of attention on a quiet holiday morning. A quarter-million people saw the tweet and a third of them interacted with it. It was enough attention that the AWS Support Twitter account was on it before, my friend and cloud economist, Corey Quinn.

Praise Twitter for at least its ability to draw attention to things. I am not sure this would’ve ended up as well as it did without it.Oh no! 😰 Sorry to hear about this unpleasant Saturday morning surprise, Chris. Please create a support case so our agents can help get to the bottom of this: https://t.co/weTUnSYLRU. 🕵️♀️ ^HG

— AWS Support (@AWSSupport) July 4, 2020

— Corey Quinn (@QuinnyPig) July 4, 2020I forwarded the bill to Corey almost immediately after seeing it at pre-dawn west coast time. I am forever thankful to Corey for his analysis. When he was ready, Corey sent me a list of things he needed to do an analysis (instead, I created him a regular IAM account with the proper perms 😉 and yes I cleaned up after).

Corey encouraged me to apply a bucket policy that would only allow Cloudflare IP addresses to access anything from the bucket. The theory here is that someone could have been bypassing Cloudflare somehow. But, thankfully, Cloudflare publishes their IP blocks and they don’t change all that often. The Cloudflare support article, Configuring an Amazon Web Services static site to use Cloudflare gives you an example bucket policy to do exactly that. This should become a standard practice for folks. However, it wouldn’t have mattered in this case; more on that later.

Corey Quinn’s thread on the topic covers what happened on the AWS side pretty well:

That's right--it's threading time!@chrisshort's surprise @awscloud bill of $2700 looks S3 driven... https://t.co/VnXufn24iA pic.twitter.com/tKLWv5rHtW

— Corey Quinn (@QuinnyPig) July 6, 2020

- “…it’s almost entirely due to us-east-2 data transfer out…”

- “Now, what caused this? Nobody knows!”

- “Chris Short isn’t some random fool…” (Might be the nicest thing Corey’s every said about anyone he’s not related to)

- “‘Surprise jackhole, your mortgage isn’t your most expensive bill this month, guess you shoulda enabled billing alarms!’ is crappy, broken, and WOULD NOT HAVE SOLVED THE PROBLEM!”

- “I want to be explicitly clear here: Chris Short didn’t do anything wrong!”

But wait! There’s more!

I had tickets in with Cloudflare (1918916) and AWS (7153956931). Cloudflare was the least helpful service I could have imagined given the circumstances. A long term user and on and off customer thinks they were attacked for two days and you don’t lift a finger? If I didn’t have reason enough to move off of Cloudflare, I do now. That’ll be an update for a later blog post. But, if you work for a CDN company and you’re relatively painless to get up and running, I’m interested in hearing from you.

After a very chaotic morning, I take Corey’s advice, disconnect, and enjoy the holiday weekend.

More Help Arrives

On July 8th, an astute AWS employee starts doing some digging around and reaches out to me. Because they see this as bafflingly as Corey and I do. How did so few requests generate so much traffic so quickly and then as soon as it appears, it’s gone again? It doesn’t seem like something intentionally malicious either because Cloudflare and AWS let it right on through.

Here’s the theory

In hindsight, I made a poor decision to distribute a trial Windows 2019 SQL Server virtual machine images (fully patched with all necessary drivers and VM extensions) in the form of a qcow2 file. Someone became aware of the existence of this VM image. They then stood up hundreds, potentially thousands, of copies this VM using the internet accessible URL. This is, in theory, possible, with something like Kubernetes and Kubevirt. Given that the disk image becomes a volume mount in the corresponding VMs pod. Spin up enough copies of the VM, a single YAML file can create infinite copies of a VM. If the YAML definition directly referenced the Cloudflare or S3 URL and not a locally cached copy, you can rack up the number of times you pull down an image real quick. The qcow2 image, in this case, was 13.7 GB. But it’s trickier than that.

The sharp edge of the cloud

File this under, “Things I should’ve known but didn’t.” Did you know that “The maximum file size Cloudflare’s CDN caches is 512MB for Free, Pro, and Business customers and 5GB for Enterprise customers.” That’s right, Cloudflare saw requests for a 13.7 GB file and sent them straight to origin every time BY DESIGN. Ouch!

I suspected these files immediately on July 4 and moved them to an internal work GDrive for the time being. If you need the images, let me know, you’re also a suspect if you ask for them, be warned.

If you’re sitting at home doing the math, something might not be adding up. The bandwidth cost is off, there was indeed some legitimate traffic to the bucket in June, of course, But, as it turns out the intrepid AWS employee discovered that 3655 partial GETs to the object might have actually been delivered as full file requests and Cloudflare might have ever done anything with them. Yes, this is a bug somewhere and folks are looking into it. I also suggested that object size limits be a tunable S3 bucket policy. This way, I wouldn’t have even been able to upload the files to the bucket, to begin with.

The Resolution

As I mentioned, I’ve removed the multiple gigabyte files from the bucket the day I got the bill (July 4). Corey pointed that out here. That might have hindered the investigation from the AWS side. I won’t be so quick to delete in the future. I will lock files down though. But, let’s face it. Now that I’m aware of the 512 MB file limit at Cloudflare, I am moving other larger files in that bucket to archive.org for now (and will add them to my supported Causes).

Long term, I won’t want to store files in multiple places. I don’t feel like archive.org should be my site’s dumping ground since it can turn a profit if it gets popular. archive.org is a stop-gap for two files for the time being. But, I could do some cleanup of that bucket now that I have proper logging enabled (oh and AWS Budget Alerts). I will also be researching user-friendly alternatives to Cloudflare even if it will cost me a few bucks a month. I will also never co-mingle work and personal file sharing EVER again.

In the end, AWS did refund all but about $40 of the $2,657.68 original bill. I wonder if I had been with any other provider (CDN included) if I had gotten a refund at all. I suspect smaller vendors wouldn’t have been as forgiving, especially given the global economic climate.