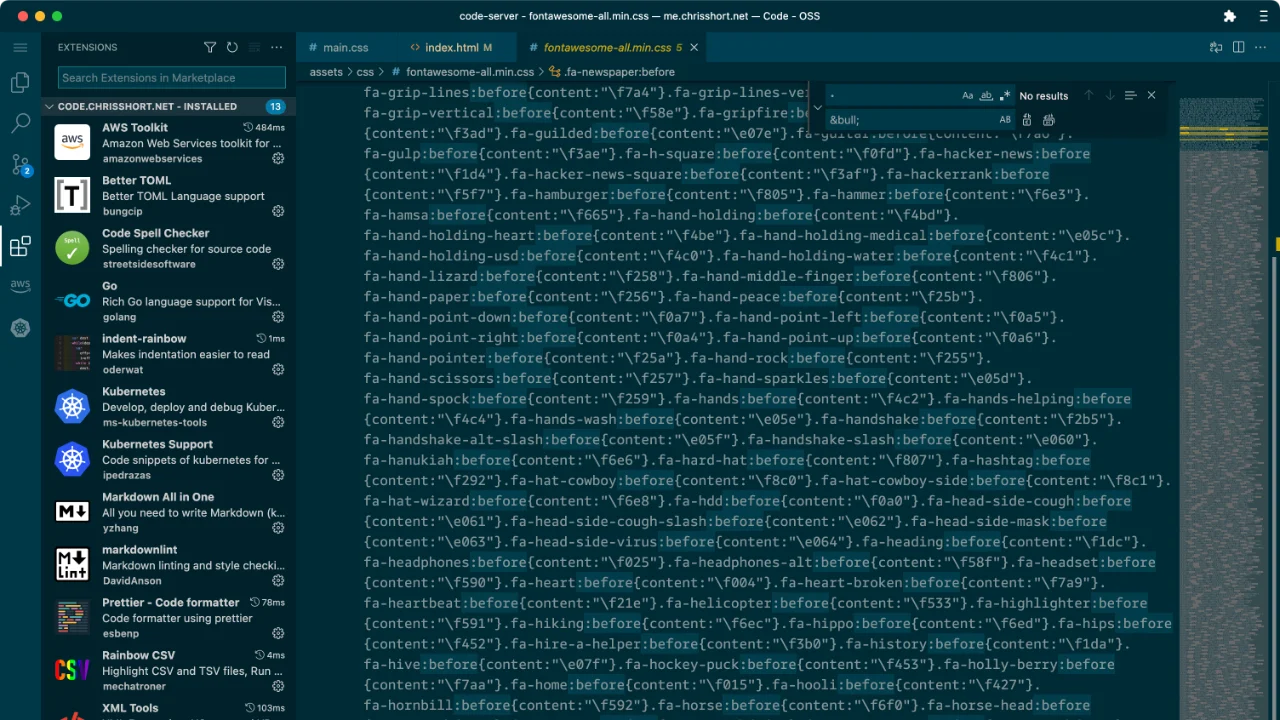

I think I’ve discovered my development environment equivalent to nirvana. code-server fronted by Caddy on a box with Tailscale installed. I maintain a lot of Hugo websites. Hugo has been my go-to content management system (CMS) since discovering it in 2017 (I got my first Hugo site at GopherCon 2017).

I’ve lost count of the number of domains I own (a common nerd problem). But, I know I have a handful of websites I update regularly. For years I’ve used the Settings Sync extension in VScode to make things consistent across machines. But something was always missing (for example, shell integration, fonts, etc.).

Requirements

While at Open Source Summit this year, I took on a small project in my free time to get a code-server of my very own up and running. There were a few requirements, though:

- HTTPS all the way: Nothing would get transmitted in the clear, no matter from wherever I’m connecting.

- Protected: The best way to not have something kicked over and abused on the internet is not to put it on the internet.

- Fast Feedback Loops: Have a similar experience as running the

hugo servercommand locally.

If any of these requirements were unachievable, I’d have to create new mechanisms to do what I could and have been doing locally for years.

code-server

First, get the code-server up and running. I chose a virtual machine (VM) running Ubuntu on my newest, fastest machine for this task. Why? I have no Kubernetes clusters up at the moment, plus font management is slightly foreign to me on Linux (and I want my nerdy fonts). I gave it six cores and 24 GB of RAM (more than enough for my needs anyway). Plus, there are plenty of tools for porting VMs to containers I could use. There are many install options for code-server. But, their install script is nice and neat, uses the OS packaging system, and “just works®.”

Remember, the goal was to create the ultimate dev environment, not the ultimate container (I’ll do that later). Once the code-server was up and running on the server (and I could connect to it). I have to figure out how to serve this up more securely. Enter Caddy stage right.

Caddy

Using Caddy is a decision on my part. I’ve heard of its dead easy configurability to learn a new web server. But I’m glad I chose Caddy because it made my life easier than I imagined. The integration with DNS providers to help manage certificates, in this case, for a web server on a private network (public DNS tough), is a killer capability. Caddy is awesome because it did this with six lines of config.

I downloaded Caddy with my DNS provider coupled as a module (being sure to select the correct system architecture; Caddy folks, this is a UX bug) and tossed that binary in /usr/bin/caddy. I also created a user for caddy, as that’s good Linux hygiene, so I ended up following the Manual Installation guide (which is delightful). Here’s the entire Caddy config for this project:

code.chrisshort.net {

reverse_proxy 127.0.0.1:8080

tls <EMAIL> {

dns <PROVIDER> {env.<PROVIDER>_AUTH_TOKEN}

}

}

That’s it! The environment variable lives in the systemd unit file (more on that in a second).

Thank you to the good folks in the Coder booth during Open Source Summit for the pointer to the Caddyfile in the docs. Next, I needed an API key provided as an environment variable (preferably only available) to Caddy to manage the DNS zone for chrisshort.net. But, you can do this with a user environment variable if you want. I try to have as few moving pieces as possible.

systemd

You can put this in several places per the documentation, but the most OBVIOUS place to me was in the Caddy systemd unit file. It’s an execution implementation, so keep it all in one place and lock it down. Here is my caddy.service systemd unit file:

[Unit]

Description=Caddy

Documentation=https://caddyserver.com/docs/

After=network.target network-online.target

Requires=network-online.target

[Service]

Type=notify

User=caddy

Group=caddy

ExecStart=/usr/bin/caddy run --environ --config /etc/caddy/Caddyfile

ExecReload=/usr/bin/caddy reload --config /etc/caddy/Caddyfile --force

TimeoutStopSec=5s

LimitNOFILE=1048576

LimitNPROC=512

PrivateTmp=true

ProtectSystem=full

AmbientCapabilities=CAP_NET_BIND_SERVICE

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

[Service]

Environment="<PROVIDER>_AUTH_TOKEN=<TOKEN>"

SECURITY NOTE

Be sure to chown root:root and chmod 0600 any systemd unit file containing credentials.

Spin Up Caddy

Run the following commands to bring up your Caddy server.

systemctl daemon-reload

systemctl enable --now caddy.service

Caddy is now handling TLS via fully-managed HTTPS (Automatic HTTPS, Caddy calls it) and proxying those requests to the code-server. All we did was add the correct module and configuration. But, wait, how do you access the server? Well, the good news is Caddy listens on all interfaces by default.

Enter Tailscale stage right.

Tailscale

For testing purposes only, my first run at this exposed the server publicly to test some things I wanted to tinker with on my network. But, after seeing all the probing traffic in the web server logs (immediately after it came online), I decided it needed to be a private service behind a VPN, not a public one. After installing Tailscale on your code-server box, update your server’s DNS record to point to the Tailscale IP of the code-server box (usually tailscale0). Folks will see the host’s Tailscale IP if they query the server record (better than your home’s IP). Since this is a private IP on the Tailscale network, no one will be able to access the code-server unless they’re on your VPN.

A brief note on security through obscurity

I’ve never understood why people think private IPs in public DNS are a security risk (I’ve even gotten a stern talking to about mentioning PUBLIC IPs in the Ansible forum at a bank once, that was comical). Unless your entire zone is private, there’s little reason in my mind not to utilize hosted DNS services. Sure, you could run a private DNS server and put the record there. But, I’m positive my DNS provider provides more nines of service than I ever could create on my own. Please let me know if I’m wrong here for reasons X, Y, and/or Z.

A fast feedback loop

Now we have a working code-server running over Tailscale and exposed with a using cert at code.chrisshort.net (but that’s a private IP that only I can access from ANY of my devices with a web browser (and I’m okay with publicly exposing an internal IP via DNS).

We need to build out that hugo server feedback loop experience. If you’re unfamiliar, by default, hugo server renders your site locally so you can iterate on it quickly and see changes occur as promptly as Hugo can compile them. Thanks to its maturity, Hugo has a TON of configuration options. I wanted to avoid having to commit to a branch and wait for Netlify to deploy my site, which is not even close to as fast as Hugo’s native live rendering.

I’ve used a localHugo script in my ~/bin directory for quite some time. I needed to configure Hugo to bind to the same Tailscale interface that we’re using to expose the web service. After reading the Hugo server docs (and a little trial and error), I attained that fast feedback loop. I came out of the endeavor with this as my localHugo script:

hugo server \

--gc \

--disableFastRender \

--templateMetrics \

--printI18nWarnings \

--templateMetricsHints \

--printPathWarnings \

--buildFuture \

--enableGitInfo \

--log true --logFile hugo.log \

--verbose \

--verboseLog \

--bind 100.88.130.127 \

--baseURL http://code.chrisshort.net

To see the live rendered Hugo site I was working on, I run this script via the Terminal in code-server and then go to the link generated by Hugo on port (1313) on the box (ex. code.chrisshort.net:1313). I’m not trying to serve that up securely, as it’s a short-lived service on an isolated machine.

I also have an alias to create a server using a quick and dirty Python command in my shell configuration (h/t Justin Garrison’s wonderful dotfiles):

alias serve="python3 -m http.server"

When I was building out chrisshort.net (to replace Linktree), I landed on a genuinely static HTML 5 template called Aerial (Hugo would be overkill for a landing page like this). But, there was no web server or live reloading on the box for this ultra-simple site setup to iterate my changes quickly. Instead of running localHugo for this static HTML site, I ran my serve command from the website’s root directory. I accessed the host over port 8000 to see my changes live without deploying to Netlify. I’ve solved the feedback loop problem between the serve alias and the localHugo script.

If I’m at home where the server is, this feels FASTER than the native experience when using hugo server locally. I attribute that to tuned and the fact that the system is an 11th Gen Intel NUC i5 with 32 GB RAM packed with a lightning-fast 2 TB NVMe drive (it’s also my streaming rig when needed and our home’s Plex server). In a few weeks, I’ll be traveling again and can’t wait to try this setup out from the other side of the country.

The cherry on top

The real cherry on top of this setup is if your browser allows you to create web apps (Chromium-based browsers do; you can do this on your iPad or iPhone, too 😎😎😎). On desktops, in the far right of the address bar in your browser, you should have an option to create an app. This gives me an app launcher for my dev environment in my macOS dock, which is terrific.

It’s wonderful, like unicorns and rainbows, y’all. 🦄🌈🦄🌈🦄🌈

Next steps

It costs nothing but the domain I already own to host this website and my email. I’m using my hardware here, too (and the associated risk I’m taking). I have security safeguards in place if something goes wrong.

But, you could easily spin this up in a cloud provider and have the same experience with many more nines (and maybe a little more latency when you’re not close to your server).

I should probably see if someone has done this before. My goal now (obviously) is to run this in a more cloud native way (a non-interactive setup for Tailscale could be hard 🤔🤔🤔). At the very least, I’m thinking of a Kubernetes namespace with proper Ingresses, Services, and (eek, local) storage (think namespace per developer environment). A stretch goal would be running it on something like AWS Fargate easy, too, so it could spin down to zero (but storage 🤔🤔🤔).

Then I’d like to strip it down to nothing and run it as a standalone pod and/or container. My list is endless. But, my next tech tinkering will be to spin up EKS Anywhere on my hardware and start porting this setup there.

Resources

All the files used for my setup are avaliable on GitHub. Feel free to submit pull requests!